La Conquista, much needed religious reformations and the invention of the printing press mark the beginning of a new period, but the most important trend was the Industrial revolution.

Modern art encompasses the Renaissance, the Baroque, the Rococo, the Neoclassical, and the emergence of Modernism.

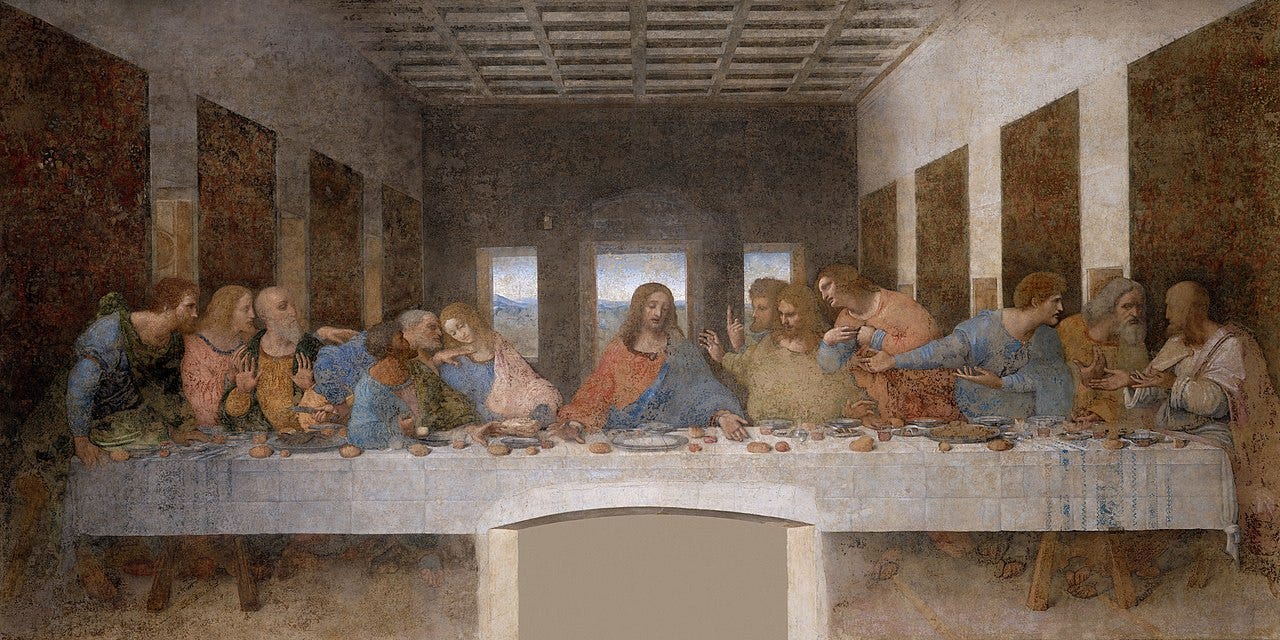

As a transition, the Renaissance (14th–17th centuries), which is centered in Italy, kept a lot of the Christian themes but focused more on the human figure and realism not unlike during the Classical period.

As a reaction, Baroque (17th century) bursts with expansive compositions, grandeur, and ornamentation. The dramatic and emotional works have a stark contrast.

Equally grand but more light and playful, Rococo (1700s) stems from the French refinery with focus on aristocratic subjects, leisure, romance, and pastoral scenes. Artists use pastel colors, soft lines, and ornate detail.

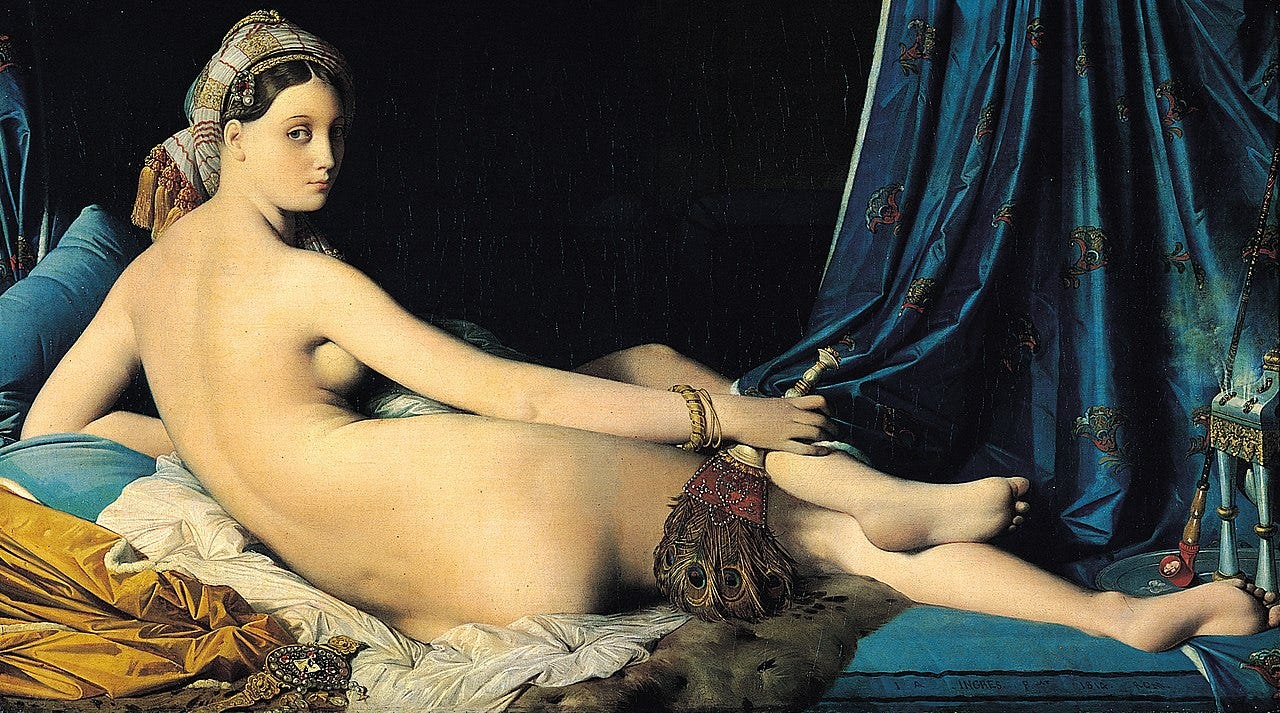

Another return to classical ideals of Greece and Rome, also centered in France, the Neoclassicism (Late 1700s–Early 1800s) put the emphasis on rationality, simplicity, and symmetry.

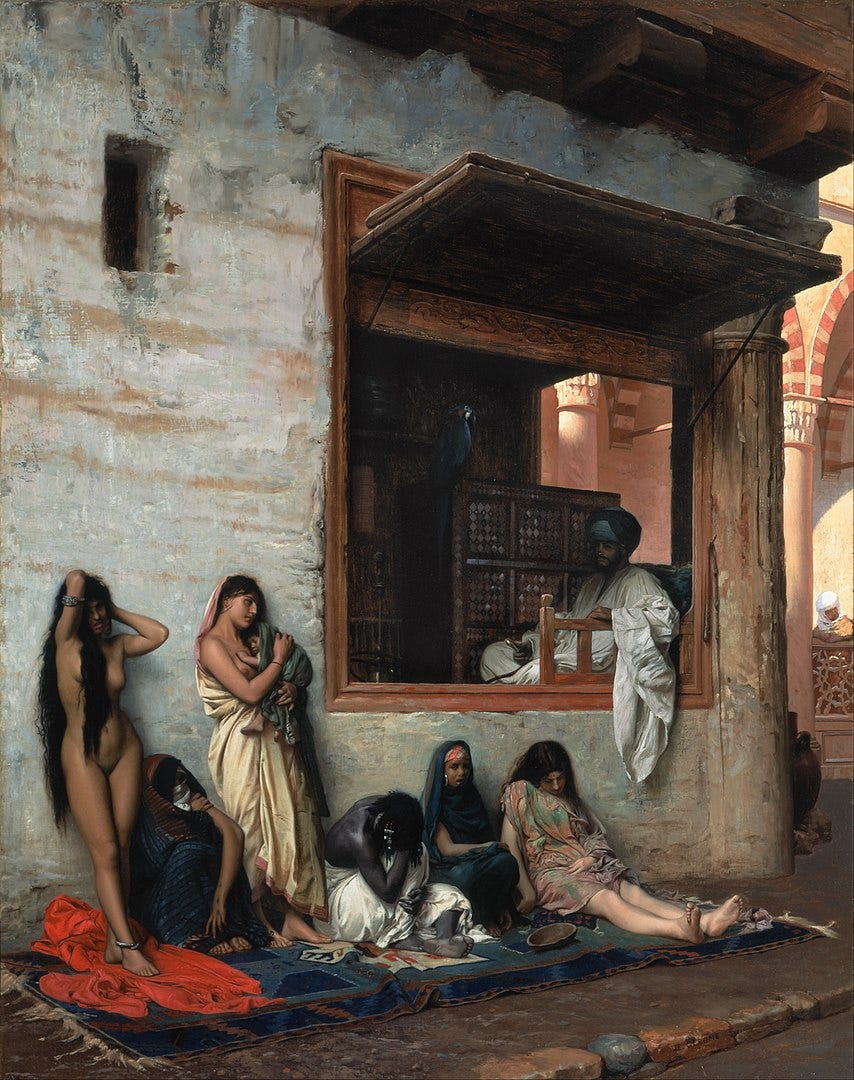

After Bonaparte's visit to Egypt along with 160 scientists, engineers and artists, the old continent is obsessed with Orientalism on one hand and colonial curiosities on the other.

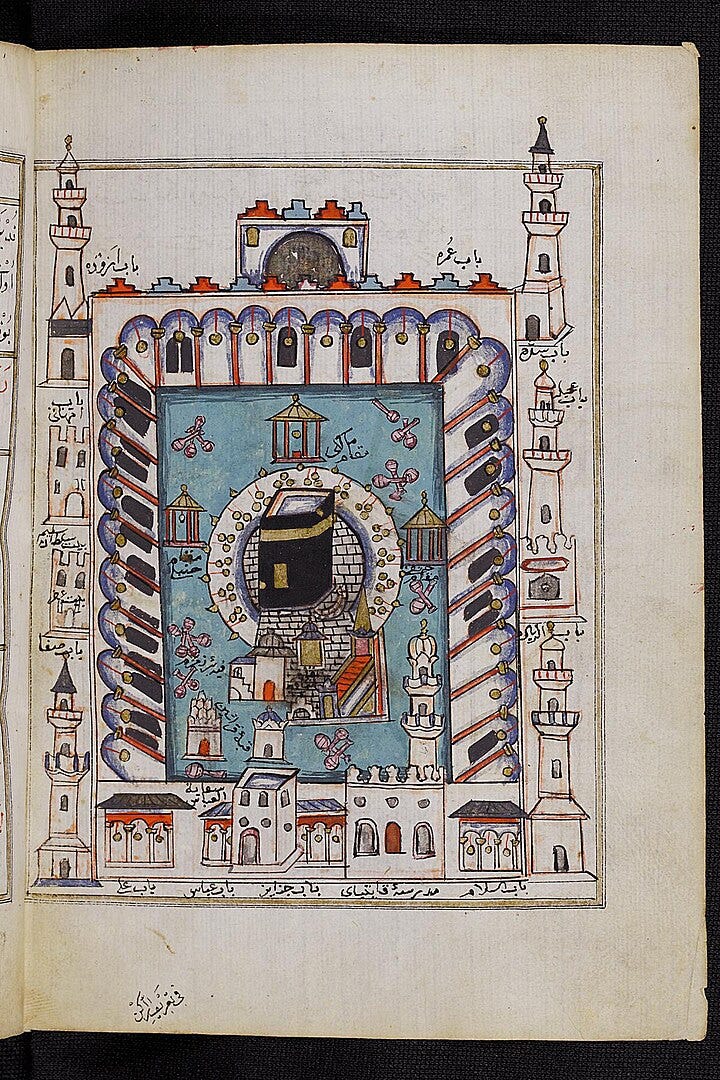

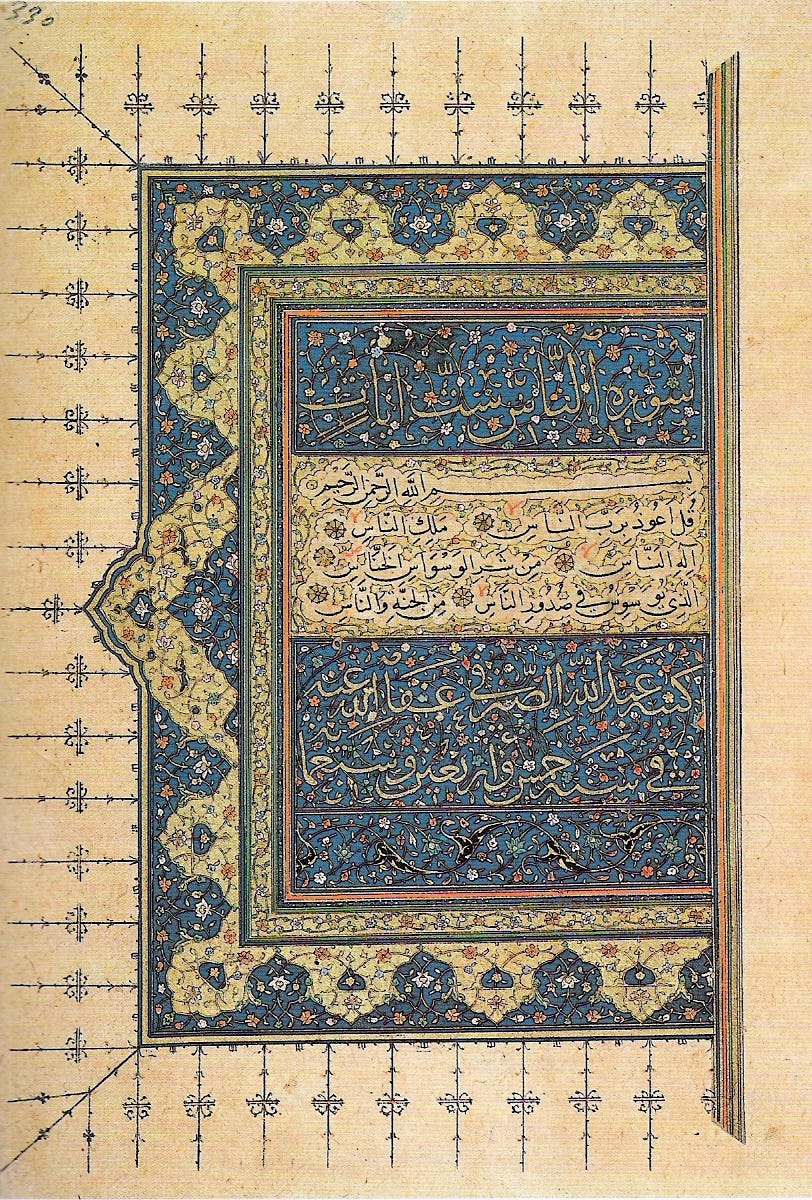

At the time to the East, the most impressive and powerful was the Ottoman art (1299–1922), combining monumental architecture like the Blue Mosque with Islamic calligraphy.

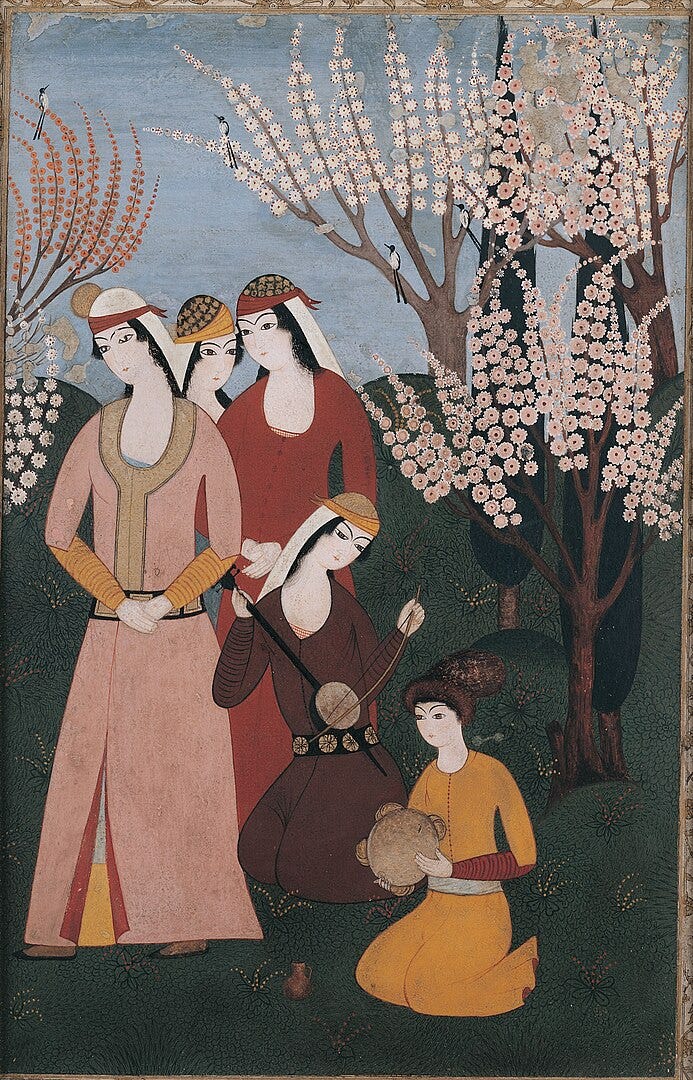

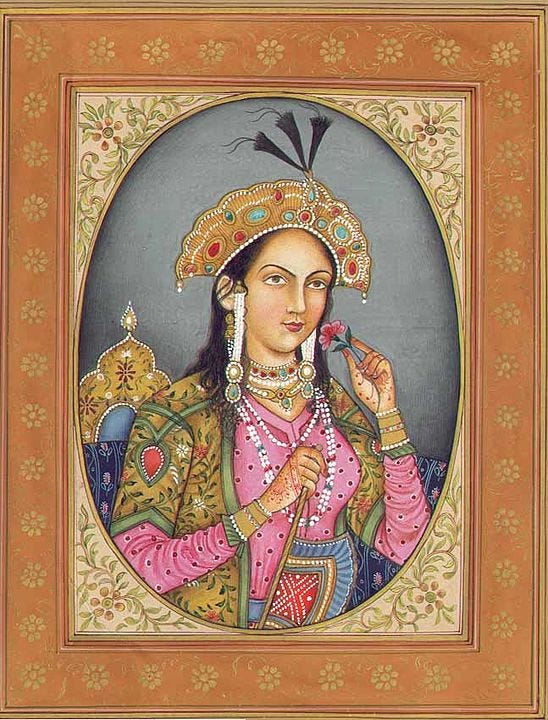

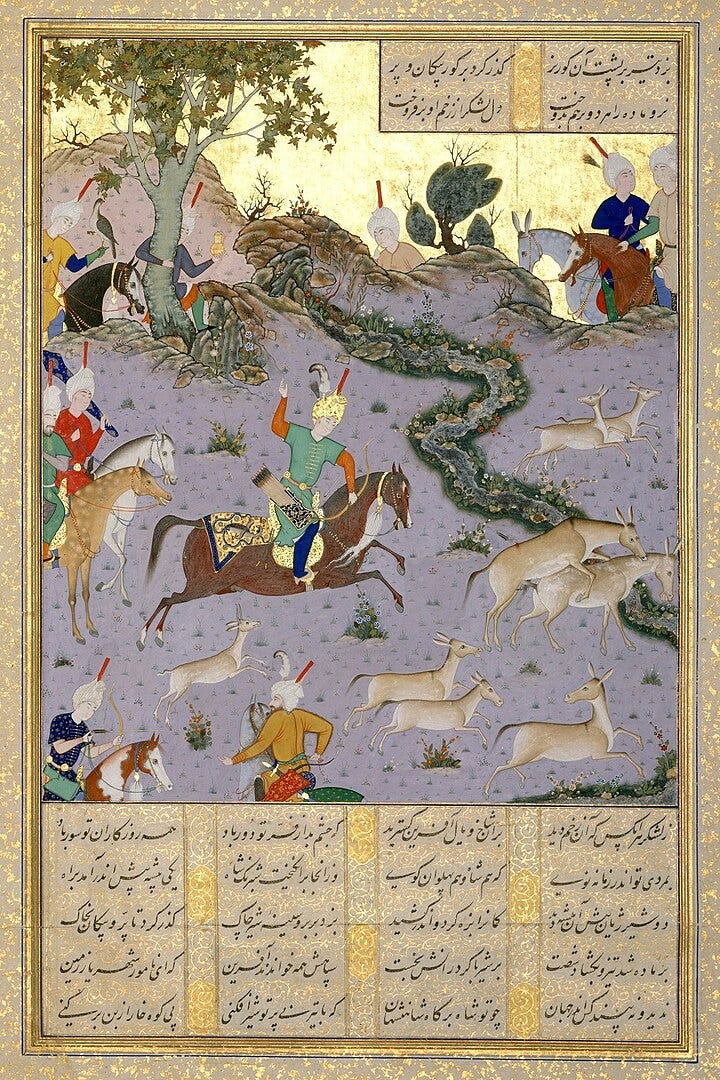

Similar trends, you can see in farther Persian art during the Safavid (1501–1736) and Qajar (1781–1925) dynasties, also famous for intricate designs of Isfahan’s mosques, as well as miniature painting.

Its style and subject influenced the neighbour Mughal empire (1526–1857) in India, whose greatest achievement is nonetheless the Taj Mahal. Then came the British (1757–1947) under which rule the British East India Company commissioned Indian artists to depict local scenes, flora, fauna, and people. These paintings are also known as "Patna Qalam" or "Company Paintings".

At later period, the Far East had a greater impact on Western tradition: particularly the Edo Period’s (1603–1868) ukiyo-e woodblock prints and rich decorative arts of Japan.

But no more prevalent during the 18th century than that of Chinese art of the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912), known for imperial porcelain and detailed scroll paintings. The craze even started an imitative genre titled “Chinoiserie”.

At the same time, a large part of the world was being invaded by the forces of the relatively tiny nations.

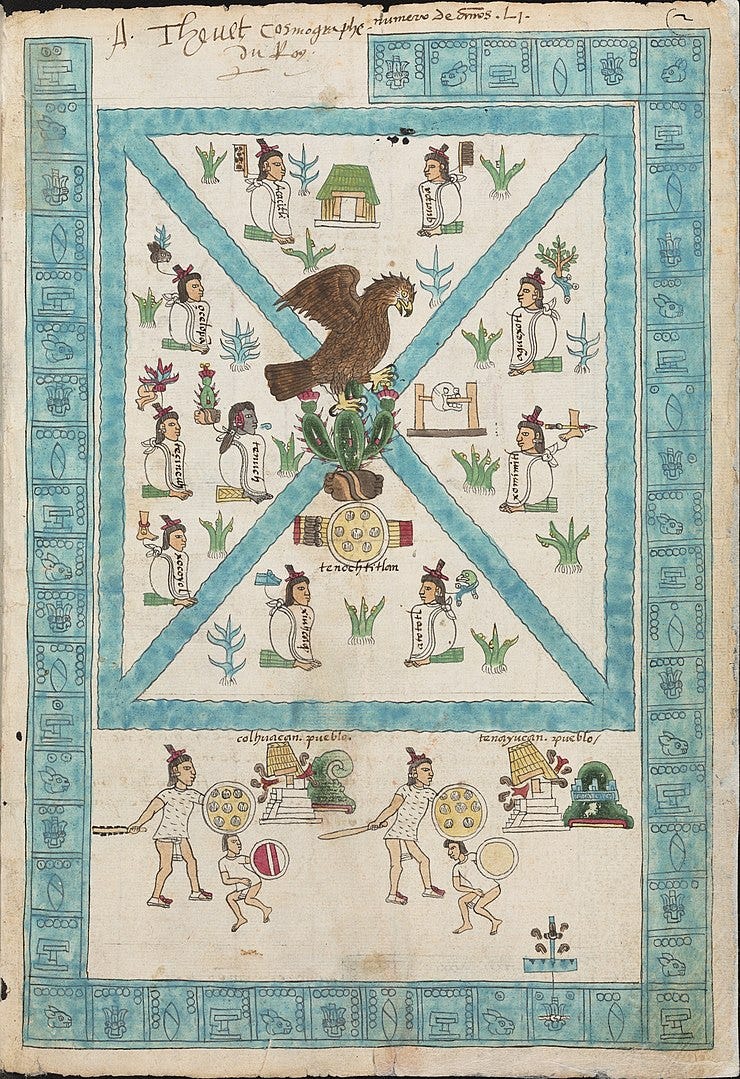

First, in the Americas, under the Spanish colonization (1500s–early 1800s), European artistic techniques combined with Indigenous and African elements. Religious art dominated, particularly Christian imagery commissioned by the Catholic church as part of the Counter-Reformation. For instance, early religious murals in monasteries used indigenous iconography to convey Christian themes.

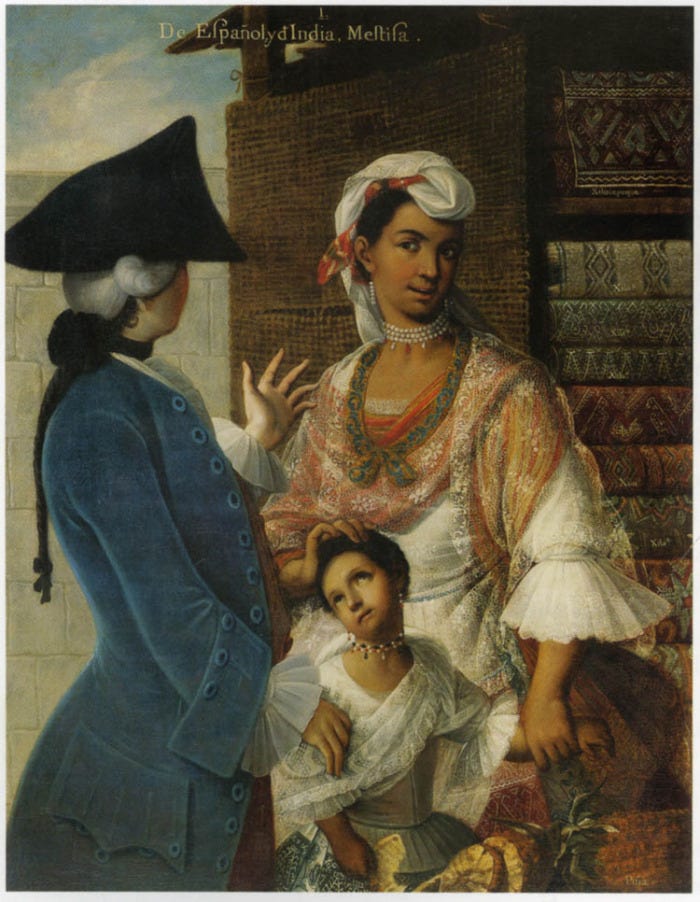

Another concern for the colonizers was establishing a clear mixed-race hierarchy, documenting the various racial combinations (Spanish, Indigenous, African) and their societal roles, which gave rise to the so called Casta paintings.

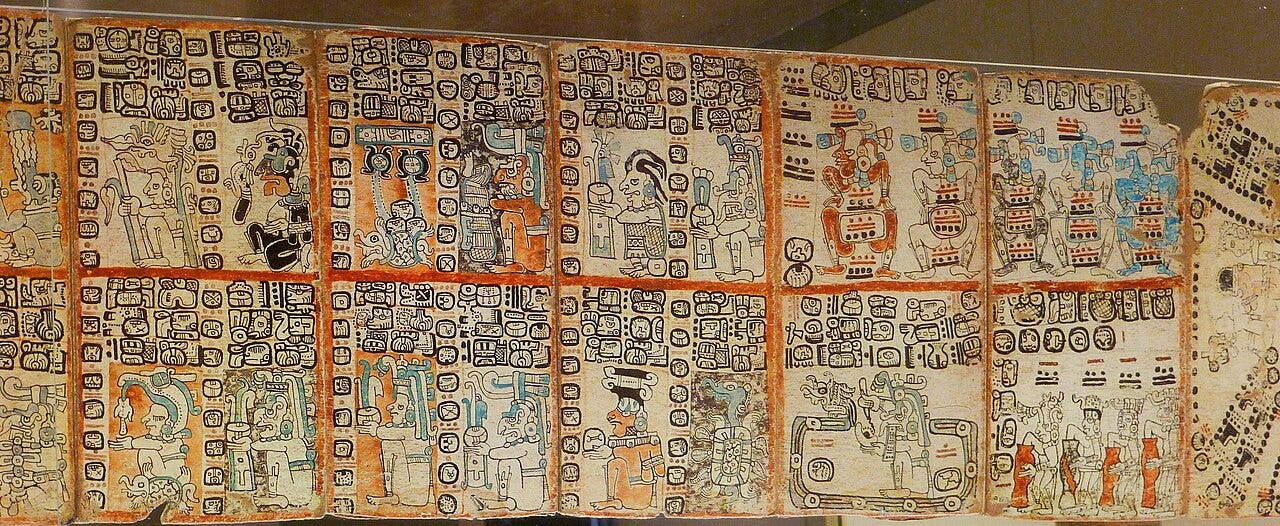

Sadly, some of previous civilizations’ artifacts were lost but we still have the Mexican Codices (15th–16th centuries), illuminated manuscripts by the Aztecs and Mixtec cultures.

Peruvian and Andean textiles continue vibrant local traditions.

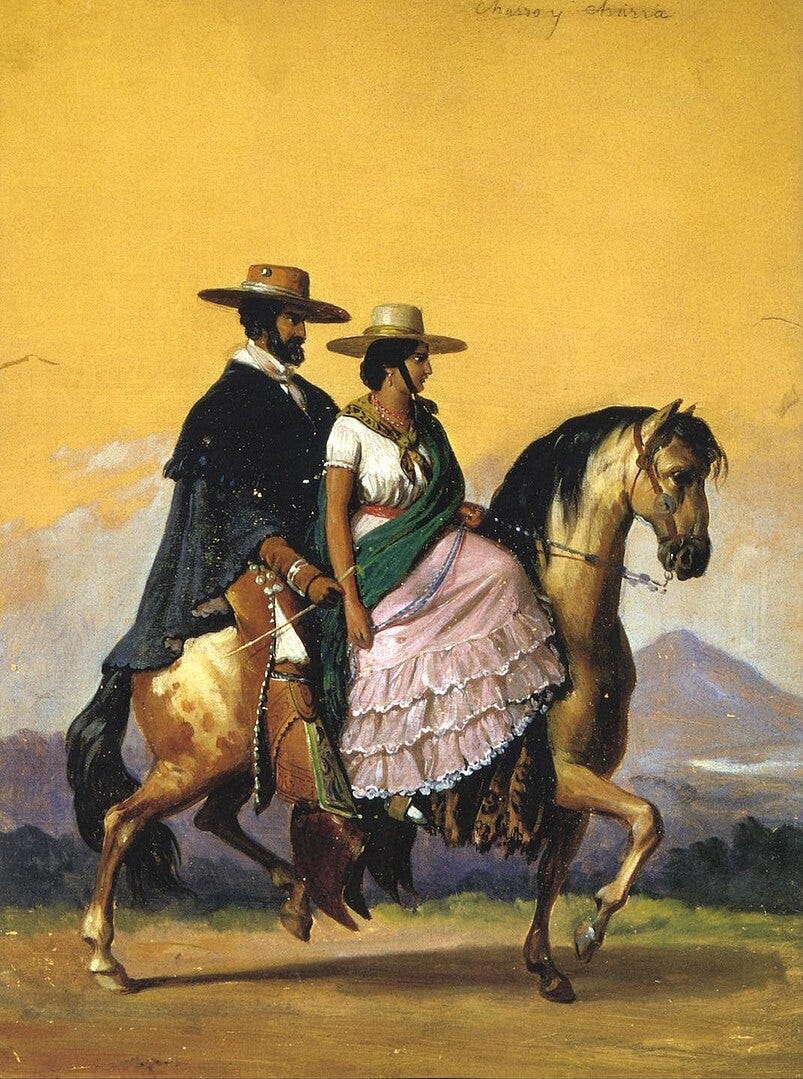

Although initially associated with Spain in the late 18th and 19th century, costumbrismo, or art with special accent on local everyday life, mannerisms, and customs expanded to Latin America, was emerging.

In Brazil, Jesuit missions created religious sculptures, often crafted by Indigenous artisans who incorporated their own symbolism.

In North Americas (1600s–1900s) there are two main powers that fought for dominance: the British (Eastern United States, Canada) and the French (Canada, Louisiana, Caribbean).

Early colonial art was pragmatic and centered around religious and portrait painting. As colonies grew wealthier, the influence of European artistic movements became evident, especially in portraiture.

Likewise, art in New France (modern Canada) and Louisiana was heavily influenced by the Catholic church, with Baroque and later Neoclassical styles dominating.

Another branch was folk art which was common among settlers. It included quilt-making, beading, birchbark crafts, weather vanes, and other decorative arts that were practical yet often highly symbolic.

On the African continent, despite pressure from British and French colonization (19th century onwards), art remained vibrant, with wood carvings, textiles, beadwork, and body art continuing to flourish.

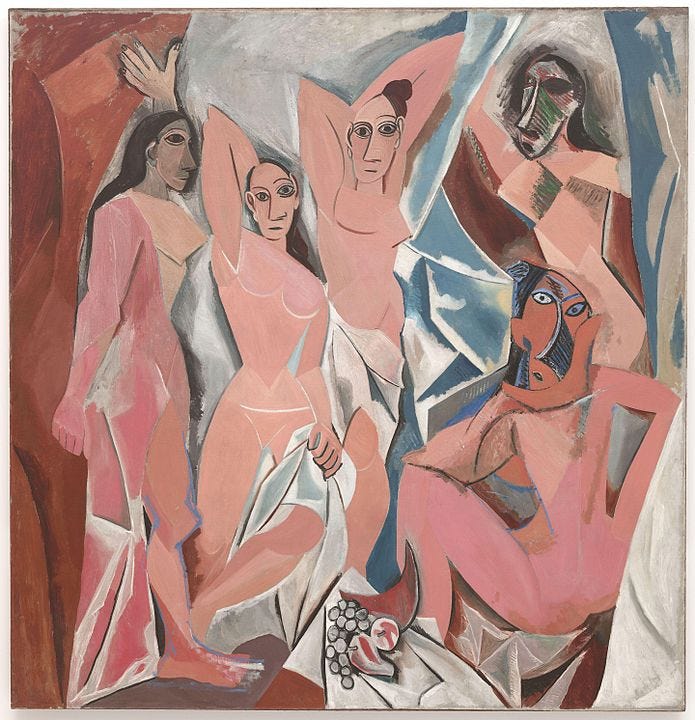

However, colonial powers often viewed African art through an ethnographic lens rather than as fine art. African artisans created objects for European markets, including textiles (like Kente cloth in Ghana) and sculptures, often modified to appeal to colonial tastes. For instance, the Kongo Kingdom produced intricate ivory carvings, blending African craftsmanship with European religious and decorative motifs, while the not commissioned by Europeans, Nkisi Figures (16th–19th centuries), used in healing and protection through spiritual power, angered the colonizers. Looted and used as payments were the Asante Empire's golden regalia and rich textile arts. Eventually, traditional African art, particularly masks, began to influence European avant-garde movements.

In Oceania, the colonization of the Pacific islands, Melanesia, Polynesia, and Micronesia, by Europeans (especially Britain, France, and later the United States) impacted the traditional art forms of these regions. Indigenous arts, including tapa cloth (made from tree bark), tattoos, and wood carvings, often reflected social status, spiritual beliefs, and cultural practices. European explorers and missionaries collected Pacific art, often removing it from its original context.

Aboriginal Australians maintained their artistic traditions, particularly in rock painting, bark painting, and ceremonial objects, even as British colonization sought to suppress their culture. Aboriginal art often used dot painting techniques to depict Dreamtime stories, representing their connection to the land and ancestral spirits.

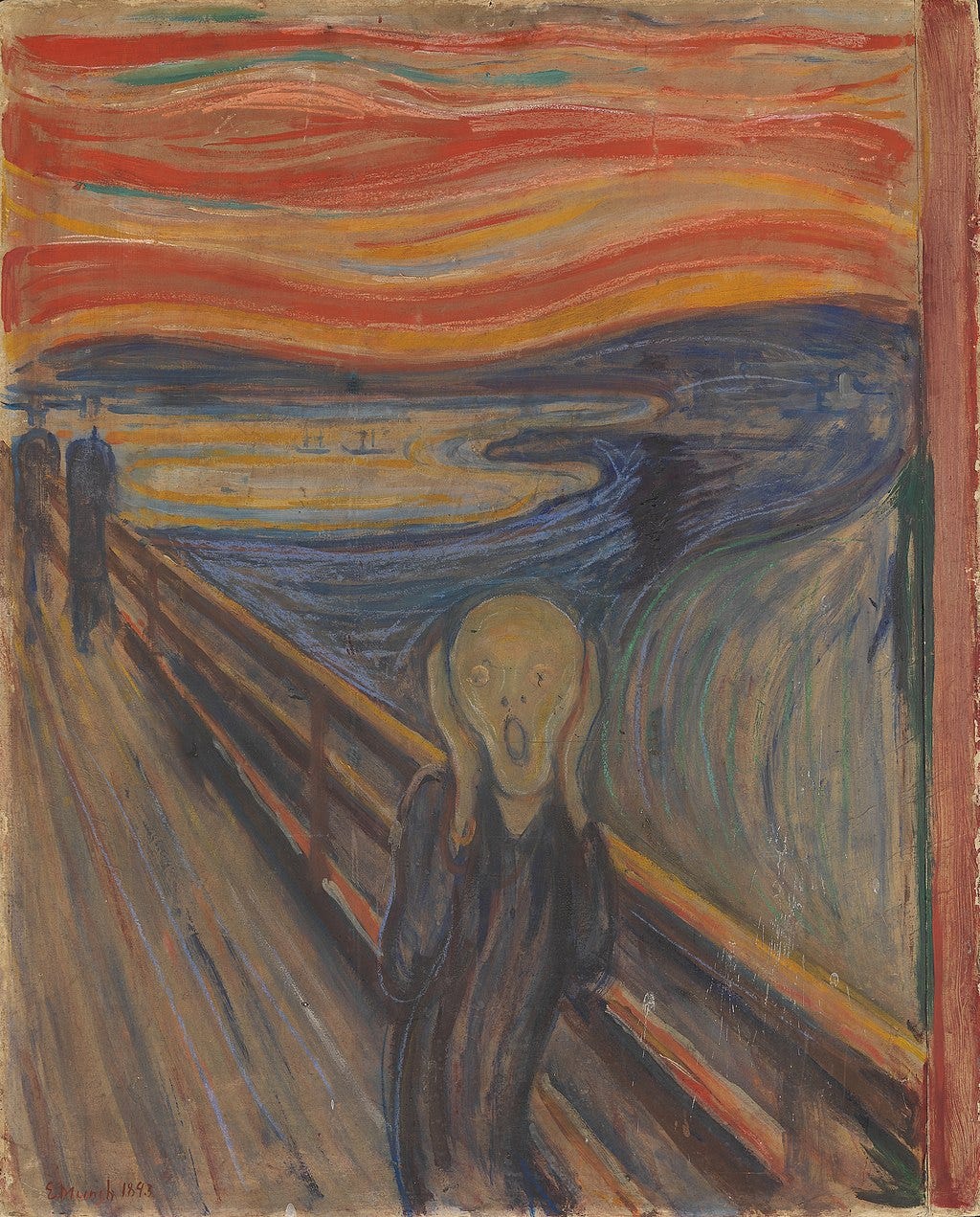

As a reaction against the Enlightenment, the 18th-century rationalism and physical materialism in general, Romanticism (late 1700s–mid 1800s) put the emphasis on emotion, imagination, and individualism. Its representatives were fascinated with the sublime, nature, and the exotic. They were moved to depict the dramatic historical events and struggles for freedom at the time.

The emotional excess that other artists witnessed, lead to the Realism (mid 1800s), which focused on depicting everyday life, particularly the working class, with unidealized detail. Its representatives didn’t hesitate to take a stance and interest in social reform and political engagement.

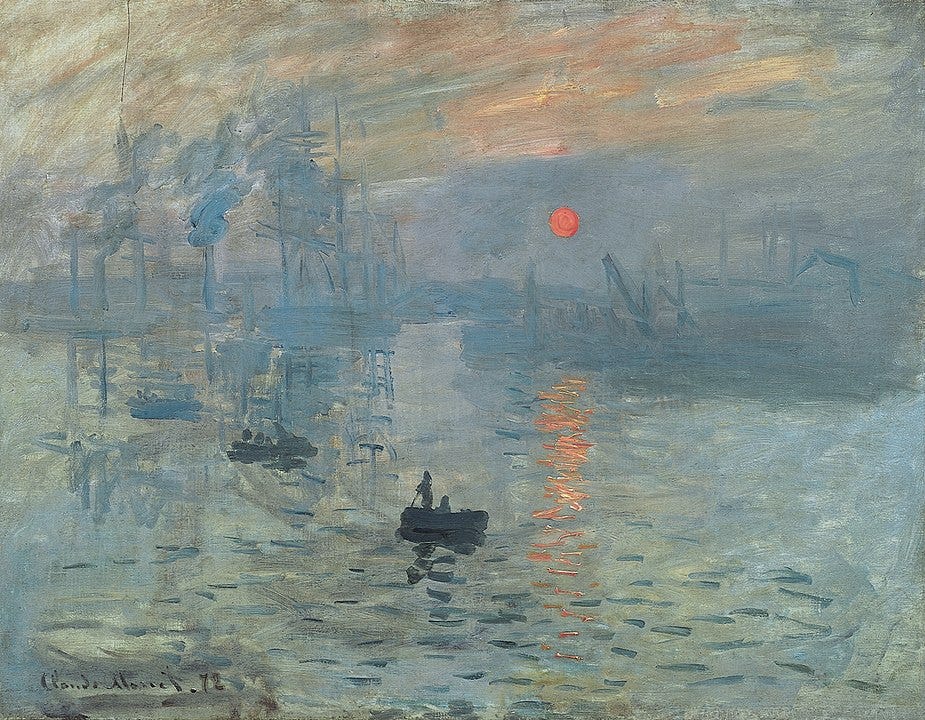

Another group that rejected traditional academic techniques and themes, formed the Impressionism (late 1800s) movement. Its representatives focused on light, colour, and everyday scenes, often painted outdoors. By using loose brushwork, they strived to catch and convey the momentary effects of light.

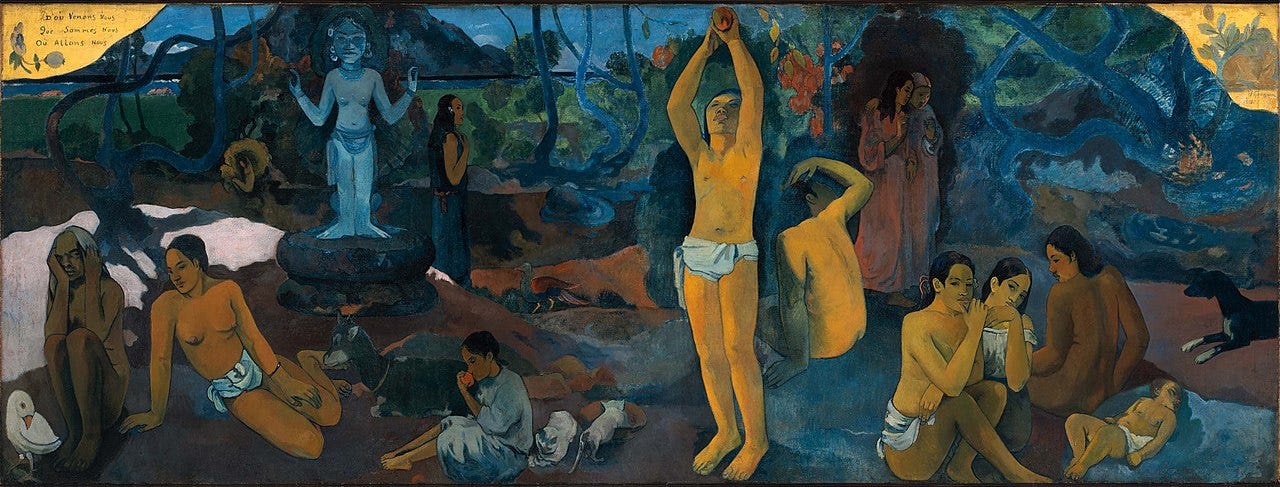

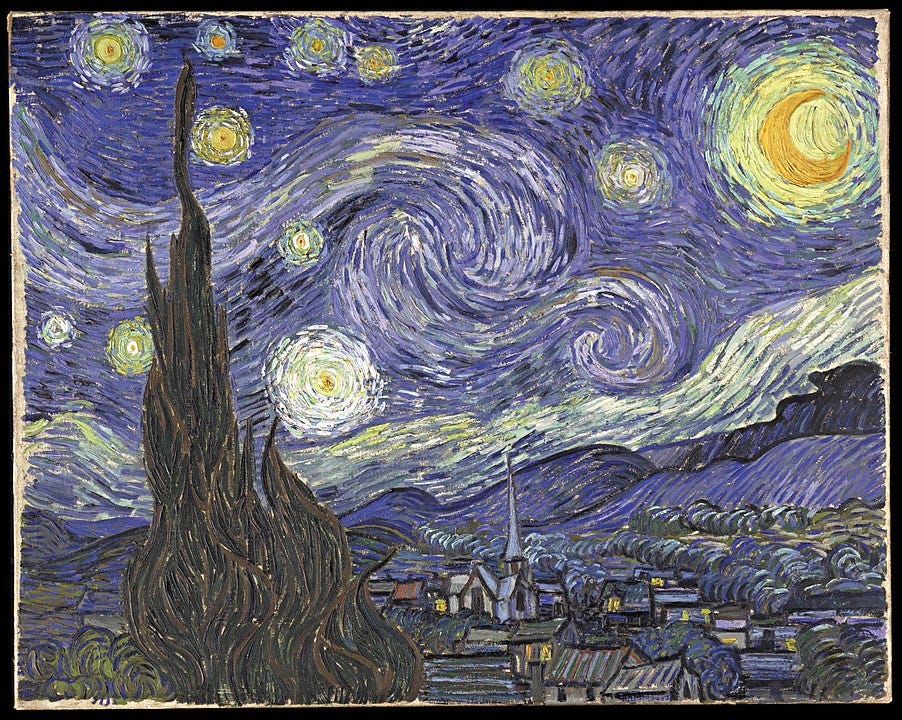

Moving beyond Impressionism with a focus on form, structure, and emotional expression Post-Impressionism and Modernism (Late 1800s–WWI) seeked to explore new perspectives, abstraction, and colour theory. Artists increasingly questioning all and experimenting with avant-garde techniques.

During this period, art underwent immense transformations: it saw the rise of individualism in the West, the expansion of global trade and cultural exchange, and the continued development of rich artistic traditions across Asia, Africa, and the Americas.

As the world moved toward World War I, art increasingly questioned traditional values, leading into the era of avant-garde experimentation.

Up next:

Art history: Contemporary art (1900–Present)

Art after the Great war saw everyone grapple with trying to make sense of the atrocities.